Cloaks, Capes, and Cappas: Historic European Outerwear

Cloaks and capes have been familiar to humanity for eons. It is technically unknown when the first cloak or cape was fashioned. Fabrics are difficult to place in archeological data but this style of clothing is so consistent in art and other sources, we’d have to look at the earliest eras of humankind to find the answer.

Instead, a good starting point is the Ancient Greeks. From there it’s possible to trace cloaks from across Europe through to the modern day.

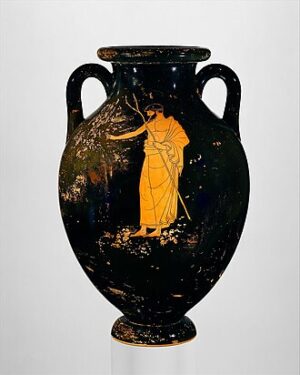

The Greek Himation

1 The Terracotta Amphora, showing a judge in a himation

After the neanderthal but in a world we would still consider ancient, the early Greeks left records of a himation. This item was initially a cloak worn over a chiton, although by the 5th century BCE it had developed into use on its own.

The himation was an uncut woven rectangle, frequently worn over the left shoulder and fastened either over or under the right arm. The style crossed over to Roman culture as a school uniform for elite sons taught by Greek scholars.

The Roman Pallium

Romans also had their own cloak, the pallium. In truth, many sources treat himations and palliums as opposite sides of the same coin.

“Pallium” gained a wide spectrum of uses, so while cloaks were palliums, not every pallium was a cloak. It could also be a bed or sofa covering, a blanket, a horse blanket, a rug, a ship’s sail, or a banner, even a shroud. (Pall is a direct descendant of pallium etymologically.)

The natural color tones of the woven fabrics—whites, greys, tans, or browns—were frequently left as-is. But the palliums could also be dyed: light green or croceus (saffron) were popular choices.

Dyes could also be used pre-weaving to create patterned palliums. Stripes, checks, and plaids were all common. Varieties with interwoven sprigs or flowers could also be found.

But the most complex of Roman palliums were those portraying historical or mythical subjects. These were considered the crowning glory of women’s abilities—associated with the goddess of weaving herself.

Decoration beyond the weave became popular, especially in Northern Europe where palliums were frequently fringed.

In nearby areas, the sagum cloak was associated with the Gauls, early Germans, and Roman soldiers. In what order that happened is unclear, but the impactful red cloak would leave its mark.

Viking and Norse Cloaks

2 Recreated Viking Cloak with Brooch Clasp

Further north, the Vikings developed their own styles and lore around cloaks. Theirs were large individually woven rectangles too, but here the resemblance mostly stops.

Vikings used wool for their cloaks. Some cloaks had layers in different colors, others were made of extremely thick wool to protect from bitter northern winters.

The cloaks could be embroidered or trimmed with braiding or left plane. Styling typically depended on the wearer’s wealth.

Wealth also influenced length, which typically ranged from knee to ankle length. Women, regardless of income, typically wore longer cloaks than men.

However, there was a notable exception: the Viking sagas reference the slæður, a cloak long enough to trail on the ground. (Here we see an early hint of long cloaks being associated with the uncanny and otherworldly.)

Another particular type of Viking cloak was the Icelandic “shaggy cloak”. The finished product had “loose” tufts of wool poking out of the fabric to achieve a truly shaggy appearance. These cloaks were so valuable that they were used as standard exchange products, like silver. Since they were such important assets, the cloaks’ production was carefully monitored but has since been lost to the ages.

Norman Cloaks: A Stylistic Revolution

Eventually, these varied cloaks came together in a single culture: the Normans. A mixed breed of Scandinavians that had settled in post-Roman Gaul, the Normans picked up traditions from all three cultures, including cloaks.

Once the Normans had conquered England in 1066, the Anglo-Saxon semi-circular mantle entered the mix as well. It is at this point that Norman style begins to develop, taking cloaks along with it.

Normans started forming cloaks. Advancing from the single piece of rectangular or semi-circular cloth, they added fabric bands fitted to the shoulders around the 11th and 12th centuries. There was still a center pin used to secure the cloak, but it was now more form-fitting.

Advancing trade possibilities in the 12th century spurred innovation along as well. The medieval era was a true heyday for the cloak and cape.

Cloak vs. Cape

A significant development was a new kind of cloak: the cape. While the words are used interchangeably nowadays, “cape” wasn’t actually a commonly used word until 1300-1450. It stemmed from the Late Latin cappa for “hooded cloak”.

The differentiation is typically drawn at length in the modern definitions. Cloaks are longer while capes are shorter and rarely have additional pieces like sleeves or hoods. Some other particular types of cloaks that gained their own names include:

- Chaperons—originally functional hoods (see our Archer’s Chaperon here), they developed into hooded cloaks fashionable among the upper class.

- Huke—knee-length hooded woolen cloaks, typically worn by men.

- Mantles—full-length cloaks made of more expensive materials (velvet or brocade), usually secured via cording.

- Royal capes—mantle cloaks with fur capes overlaid, these were only worn for ceremonies by, you guessed it … royalty.

Medieval Outerwear Choices

The growing trade options during the Medieval era meant that the stylistic possibilities for cloaks grew greatly. From fabrics to fasteners to finishing touches, here are just a few of the medieval options for cloaks.

Fabrics

Wool—generally accepted as the most common medieval cloak material, wool was relatively easy to produce and very efficient at warming in cold weather.

Linen—harder to produce but another more common cloak material.

Cotton—was not nearly as accessible as it is today, but Italy and Spain did export cotton to the rest of Europe.

Fur—considered barbaric initially, fur eventually found its cloak production niche as a lining and edging material.

Scarlet—a more expensive woolen fabric because it was dyed a bright red (a trace of those sagums hanging on).

Eastern silks—Italian merchants imported silks from Eastern countries. Italian silks, taffetas, damasks, and velvets—Italian textile producers learned to emulate the fabrics their merchants imported particularly well, gaining Italy a foothold in the medieval fabric industry. (Velvet cloaks remain a popular style!)

Fasteners

Pins—the oldest solution to fastening a cape, still going strong in the medieval era

Cording—another long-term solution still going strong.

Buttons—the Normans had instigated this development; it wasn’t quite as popular as the others.

Brooch(es)—the elite’s playthings, brooches were generally removable and could be used with whatever cloak was today’s choice. Brooches ranged from large single pieces to two interlocking pieces or two that secured cording for a combined fastening effect.

Optional Pieces

Arm slits—these allowed for easier mobility, if colder arms … which led to the next development.

Sleeves—some later cloaks had attached sleeves.

Hoods—cloaks had long been used with separate hoods, but attached hoods gained popularity during the medieval age.

Liripipe—the liripipe was a particular type of hood that was trailing or elongated.

Finishing Touches

Embroidery—an ever-popular finishing step, the embroidery was often limited to an edging band but could encompass the whole of a cloak in extreme cases (aka Queen Elizabeth I).

Gold/silver thread—used in the upper echelons for finishing/embroidering cloaks.

Mottoes (jeweled bands)—bands of embroidery with inset jewels or pearls, very likely to use gold or silver threads too.

Fur trim—ermine is one of the most recognizable furs used to line medieval cloaks, although a wide range was used.

Linings—used as either a practical second layer or a luxury addition. Either way, lining fabrics were a common part of cloak-making, like our linen velvet cloaks.

Elizabethan Cloaks

3 The Armada Painting of Queen Elizabeth I

By the Elizabethan era, cloaks were fully stylized pieces of art in their own rights. Some of the most famous paintings of Elizabeth I display heavily embroidered and lined cloaks, often replete with gems or pearls.

While this profusion was an excess of the style fit only for paintings, the concept was absolutely familiar to high fashion of the time. It is still hotly debated whether Walter Raleigh actually dirtied his cloak on the queen’s behalf.

The coat began to overtake the cloak in popularity (possibly because of the fitted sleeves?) during Elisabeth’s reign. But it never quite managed to oust the cloak and cape entirely.

Cloaks and Capes: 1800s-Today

4 Victorian Paper Doll with Blue Cloak (1840-60)

Through the Victorian era and into the 1920s, cloaks and capes retained a niche in evening attire and formal wear. Victorian opera houses and early Hollywood red carpets call to mind flowing cloaks and shorter fur cape.

They were still a familiar enough part of elite attire in the 1940s and ‘50s when they started being adopted by a new group: the comic book superheroes. Reimagined in vividly colored plastics, even today Superman doesn’t look quite right without his cape (although let’s be honest, it’s become a cloak recently…).

Cloaks and capes retain their appeal today. They still pop up in formal or evening attire, with Lady Gaga bringing a cloak back to Hollywood red carpets for The House of Gucci. Any Renaissance fair or Comic-Con will have a fair share of cloaks and capes for a variety of LARP or cosplay purposes.

However, this author’s personal favorite was the college student she once met in downtown Seattle who consistently opted to wear a cloak instead of a coat, even during Winter Quarter. Bringing the dramatic swish of a cloak into the 21st -century everyday should be reason enough to own a cloak.